Dr. Pruthi discusses the issue of mental health stigma and why physicians are reluctant to seek care

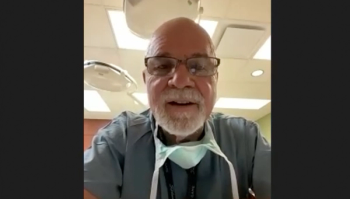

In an interview with Urology Times, Raj S. Pruthi, MD, MHA, FACS, discusses the long-standing stigma of mental health and seeking care for emotional distress as a physician.

The field of medicine is one full of stress and anxiety, but that doesn’t mean that physicians should “tough it out.”

In speaking with Urology Times, Raj S. Pruthi, MD, MHA, FACS, discusses the long-standing stigma of mental health and seeking care for emotional distress as a physician. He additionally advises on how physicians can better manage and prioritize mental health. Pruthi is a professor and chair of the department of urology at the University of California, San Francisco.

What are the stigmas surrounding mental health conditions and seeking help for these conditions?

The question that you're asking is: What prevents us from healing our healers? I believe we have an unwritten code in medicine, and in surgery in general, about never showing weakness. That may create wrong perceptions, creating this perceived stigma associated with burnout or depression. This may limit seeking help.

There are also concerns of confidentiality. Unfortunately, in medicine, we place a low priority on our mental health despite the evidence of untreated mood disorders [and] the high risk of suicide in physicians. There's a saying that the cobbler always wears the worst shoes, and I think sometimes we may be doing the same thing in medicine. Too often, I think depression is untreated until patient care is impacted. I think, as I mentioned, for physicians seeking help, there may be negative repercussions, discrimination in licensing, loss of privileges, and hindrance to professional advancement, despite having ready access to colleagues who can help us. Regulatory and workplace barriers dissuade those of us who need it from seeking help.

We often encourage our patients to share concerns about depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions, yet are less likely ourselves to seek help due to this issue of stigma. People have talked about what might contribute to this. One is potentially our "physician personality." We are often defined by things that may be attributes of being a good doctor—attention to detail, leaving no stone unturned, always thinking about our patients. But this also can be a double-edged sword. We may be those that are most dedicated to work may be most consumed by it. In addition, we're programmed often to cope alone, we have busier schedules, higher productivity, [and] more time spent documenting, which often means less time interacting with other physicians. So, we tend to be alone when we have to handle stress and don't want to reach out because we, again, don't want to look weak or [like] a subpar doctor. Interacting with others has always been part of our fabric, but that is being lost. A few aspects are [that] we often have a survival mentality. "If I can just get through residency, things will get better. Once I'm done, if I can just get my first grant or get promoted or become a partner, it will get better. Just work now, then retire, and we'll get a personal life later." [All these thoughts] can be counterproductive [and they] contribute to issues around stigma.

How do these stigmas impact physicians with these mental health barriers?

I personally believe we judge each other too frequently for having mental health issues. As I mentioned before, if we disclose it to our colleagues and seek help, they'll judge us as weak or less capable of doing our work [and they] may betray our confidentiality [or] put our careers in jeopardy, especially with the hospitals or the licensing boards. Even though we're susceptible to this, including the tragic outcome of suicide, which is at least 3-fold higher in physicians and other professionals, we're the ones who sit on medical boards and credentialing committees. So, we're the ones who decide who gets accepted or not, and who gets promoted or not. We are the ones who potentially perpetuate the stigma associated with it through judgment of our peers, residents, and medical students. This is something I think that we need to reverse.

What are some resources that you would recommend for physicians to better manage their mental health?

I'll first mentioned things that don't necessarily work well. Often, there are programs and health care systems [that] focus on physician resilience and wellness, which is really the symptom of burnout and moral injury. They create forums that discuss problems and symptoms we face—elective or urgent support programs. I've been at institutions that have programs such as "code lavender," or "taking care of our own," which all are certainly positive and strive to ease the provider stress and improve physician resilience. We hire wellness officers, create wellness programs to alleviate these symptoms and [provide] support, but they don't really address the underlying causes and they don't address issues around mental health. Thereby, [they] are limited. If you just focus on the symptoms, it's a bit short-sided and a band aid for a deeper injury. I've heard it said: "You can't be yoga your way out of burnout or mental health." These websites [and] institutional programs can be great, but limited. Beginning with online or institutional resources to become comfortable that you're not alone is important, because you're not alone. Beginning with having discussions with a trusted colleague can be beneficial. The other thing I've seen [work] positively is the involvement of primary care physicians [PCP], who have become very well-versed in providing mental health treatment and support. So, you don't need to find a psychiatrist, but your PCP can support this also. Often in surveys, physicians have said that one of the issues that they face is the ability to find an appointment that fits their schedule. I think 70% of physicians say [that not finding] an appointment that fits their schedule is a concern. So, sometimes just going to your primary care physician can be positive.

How can urologists destigmatize mental health conditions and seeking treatment for them?

That's a good question because that's the issue: How do we get there in our field? First, I think we can speak up and tell our stories. This segment by Urology Times® is a great step—an outward discussion of what the issues are. Second, we can advocate with our state government bodies, medical boards, and even our hospital credentialing committees, which still sometimes ask inappropriate questions about our mental health. Back when I applied to medical school, I remember [that] one of the questions on the medical school application asked if there's a family history of mental health disorder. So, again, [that is just] showing that this can be a stigma. Third, we can expand our perspective of mental health disorders. A narrow perspective can lend themselves to unidimensional statements, such as, "Mental illness is a weakness," or mental disorders are brain disorders. Unfortunately, this type of reductionist thinking or [these] models of illness can contribute to misunderstanding and the stigma we've talked about. Fourth, we can potentially change the use of this stigmatizing language. Labeling people as having mental disorders may unintentionally categorize them as a social outgroup subjected to discrimination and disadvantage, rather than to inclusiveness and equity. Instead of characterizing them as issues of mental health and mental illness, this condition should really be part of a continuum. The World Health Organization describes mental health as more than the absence of mental disorder or illness. It emphasizes mental health as a state of well-being, in which individuals realize their own abilities, cope in normal stresses of work, productivity, [and] life, and ability to contribute to the community. I've heard someone suggest that maybe we should talk more about emotional health and mental health, because we all have emotions, whereas we don't have mental disorders. Feeling stressed or having emotional distress may sound more acceptable than having a mental disorder.

Is there anything else you feel our audience should know about this topic?

I would encourage urologists to talk about this in their group practices as part of their practice meetings, bring in people, and use trusted colleagues. Those who are leaders in our groups or practice can also take an important step. We need to accept this as important by admitting that we're better for our patients when we're alert, focused, [and] ready. We need to cultivate habits of awareness and renewal. And, as I mentioned, we need to lead from the top down, setting good examples of good health and balance for the young partners and faculty, and for our learners. It's been shown that after 1 year of medical school, medical students already have significant burnout and depression, which they didn't have before starting medical school. And remember, in all of this, we are part of the organization, we are teachers and administrators, we need to set the example, and we need to be part of the credentialing groups or the medical boards that can make the difference and destigmatize. Our younger partners and learners need to see that in order to provide the best care for our patients, we must do everything we can to stay physically and emotionally healthy. We can be the role models for this.

Newsletter

Stay current with the latest urology news and practice-changing insights — sign up now for the essential updates every urologist needs.